the silk

history

of sericulture

Around the VII millennium a.c., sericulture has its origin in China. A legend tells that empress Xi Ling Shi, married to emperor Huang Di, was drinking tea in the shade of a mulberry tree when suddenly a cocoon fell in her cup. Soaked with hot water, the sericin dissolved, unwinding the silk filament and giving birth to the first silk thread. For many years, the procedure to produce it was kept secret, until the art of producing silk expanded in Japan, Korea, India and Europe.

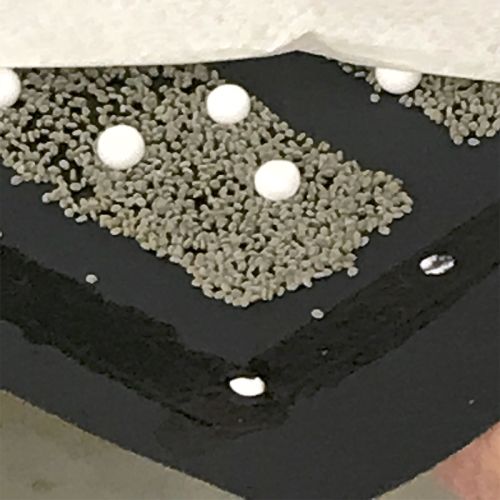

Bombix Mori’s eggs, called seeds, usually hatch in Spring, when mulberry’s leaves are already completely formed and harvests can be protracted until Autumn.

Silkworm

Depending on the climatic zone, harvests can be 2/3 up to 8/10 per year. During its larval phase, the silkworm only eats mulberry leaves, which need to be finely chopped. In about 27 days, these insects grow from few millimetres up to 7/8 cm.

At this point, the silkworm is ready to build the silk filament of its own cocoon by extrusion. The filament is contained in the two silk glands, also called spinnerets, which are located on the sides of the intestine and are divided in three portions: posterior, median and anterior. These are called “secretor canal”, “tank” and “execrator canal” respectively. The two secretor canals coming from the spinnerets meet in the so called “spinning mouth”, which is a very small opening in the face of the silkworm.

From each spinneret, a very thin and mellow filament gets out. This is called floss. During the spinning, the two flosses weld together thanks to sericin (silk’s gum) and assume a solid state as soon as they meet air.

The silk filament is produced passively, as it is not due to the compression of the sink glands, but by the circular and repetitive movements of the silkworm head. Therefore, thanks to its movements, it can continuously produce the filament.

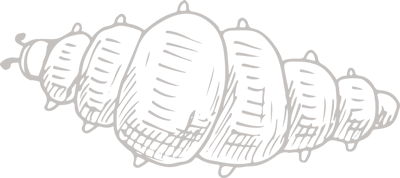

the

cocoon

As the five larval phases are over, the silkworm goes up to the cocoonery, which means that start to build its own cocoon starting from its scaffold, made of little loops and eyelet. About 20 loops form a surface layer, whose dimensions are 4-5mm. Many layers form the whole structure of the cocoon. The layers are irregularly positioned but the continuity of the yarn is not interrupted. The different layers of the cocoon are also called “clothes” or “pages” of the shell. Layers are usually 5/6 in number, depending to the race. The most common races have a cocoon made of a single, continuous filament, whose length varies from 500 to 1200 metres.

Comme nous l'avons dit, la « spelaia » est la première partie du fil extrudé du ver à soie, environ 40/50 mètres, après quoi elle commence à construire le cocon proprement dit. La partie externe du cocon, appelée « strusa », a une longueur classiquement mesurée en cent mètres. La partie centrale, dite « filable », est celle qui intéresse la filature car elle représente la partie dans laquelle le titre de la « bavelle » est plus régulier, la longueur varie selon les races et les facteurs climatiques et d’élevage ; il peut varier de 450 à 1 000 mètres.

When the silkworm is about to finish, the counts size of the filament starts tightening more and more. Finally a remaining thin layer of the cocoon cannot be reeled anymore and its lengths is about 70/80 meters. Obviously, all these values are approximate, as there are many different races of Bombyx Mori and also different climate zone in which the silkworm is raised. Under the microscope, the yarn appears made of two distinct proteinic elements: fibroin and sericin. The fibroin constitutes the silk heart and its essential part for 70-80% of its total weight. The sericin covers the fibroin like a protective sheath and accounts for 20-30% of the weight of the whole silk. The remaining part forms less than 2-3% of the weight and they include fatty, waxy, coloured and mineral materials.

For the industrial use of cocoon in the reeling mill, the chrysalis needs to be dried before the silkworm completes its metamorphoses, transforming itself into a butterfly and holing the cocoon irreparably. For this reason, in the past, the cocoons were treated in steaming stoves, where they were steamed through hot water’s vapours. Then, the humid cocoons were placed on wide, well ventilate stands. Here they could be dried up until they lose 1/3 of their weight. At this point, the cocoons can be commercialized, as they are completely dry. Nowadays, quicker and more efficient techniques have been developed, such as dry stoves, in which specific dryers are used. This also allows to dramatically decrease the appearance of molds.